Sack - The First Family of American Antique Furniture

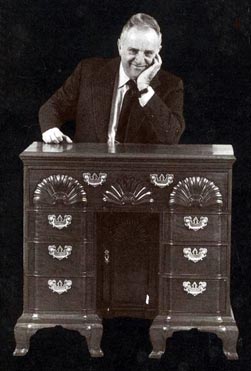

The mustard seed of antique advice I have for you this week is to locate a copy of American Treasure Hunt-The Legacy of ISRAEL SACK and read it. It's an extraordinary rag-to-riches book filled with wit, charm and insight into the exciting world of early American furniture. Additionally, it provides a glimpse behind the doors at a family that has earned universal acknowledgement as the most important dealers and scholars in the field's history. Co-author of that book, one of Israel Sack's three sons, Harold Sack died this past July 8, age 89.

Israel Sack emigrated from Lithuania to Boston in 1903 and began his career as a cabinetmaker and furniture repairman. At that time American furnishings and art were scoffed at by connoisseurs who preferred finer fancier antiques made in Europe and other parts of the world. Museums virtually ignored the field. Sack recognized something distinctive in the American pieces on which he worked. The workmanship was superior. No wonder, for the men who crafted that furniture had been freed somewhat from the restriction of European of gilds and class paternalism. From that shop where an artisan's own name hangs over the door-proud work comes.

Israel also recognized that it was in its line and proportion, not in the ornament, that American craftsmen excelled. Vertical line was emphasized over horizontal. Just as an egg appears more beautiful standing upright than on its side. When asked how he distinguished American piece from its English prototype, Israel replied, "That's easy. By its accent." Soon Israel's Charles Street shop was a destination for high caliber buyers and sellers of preeminent authentic Colonial and Federal American furniture including collectors Henry Ford and Henry du Pont. "The best to the best," Israel would say. As Harold describes in his book, many dealers referred to his father as "Crazy Sack" a name he earned for the high prices he cheerfully paid and even higher prices he then sold those masterpieces. Success can be a bumpy ride, however. More than once last century, defeat knocked on the door at Israel Sack Inc.

With the family business near to bankruptcy due to the Depression, Harold joined as president and CFO in 1933 after graduating from Dartmouth magna cum laude in English. In the next five years, and then five decades, the Sacks would help to build some of the most important collections for museums including: the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, Colonial Williamsburg, Winterthur Museum and three entire galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Private customers included the Kennedys, Bill Cosby, the Rockefellers, Ima Hogg, Paul Mellon, C.K. Davis, Landsdell Christie, George and Linda Kaufman, Joseph Hennage and E. Martin Wunsch. Any dealer getting invited on a "housecall" to these residences would wisely put other business aside.

As stated in the trade paper, Antiques & Arts Weekly, Harold Sack once told Litchfield dealer Peter Tillou," One day, a piece of American furniture will bring over a million dollars, like paintings do."

- Harold has been described as introducing to the modern world of antique business a level of integrity that none of his competitors were ever able to equal.

- It was said he could appreciate a $2,000 chair as much as a $2,000,000 chair.

- He was described as having an extraordinary eye and encyclopedic memory.

- He had a wonderful sense of humor and great interest in subjects other than antiques.

- He loved to share his knowledge and was extremely generous.

- He had an impish smile and sparkling eyes

- He could spot a fake from 50 feet.

- Harold and his brothers, Albert and Robert, took the reins from their father and brought respect to American furniture and decorative arts.

- Harold wasn't afraid to pay for a supreme example.

In 1989 a nine feet tall boldly carved bonnet-topped mahogany secretary made by 18th century Newport, RI cabinet maker John Goddard came up for auction at Christie's in New York. The stunned audience watched as the winning bidder paid more money for it than any article of furniture, American or European, had ever brought at auction. At $12.1 million it was then the highest price ever paid at auction for an object other than a painting.

"Not all masterpieces hang on the wall," the winning bidder said. His name was Harold Sack.